Opinion

Transition to sunset: the future of foreign aid for basic health services in Africa

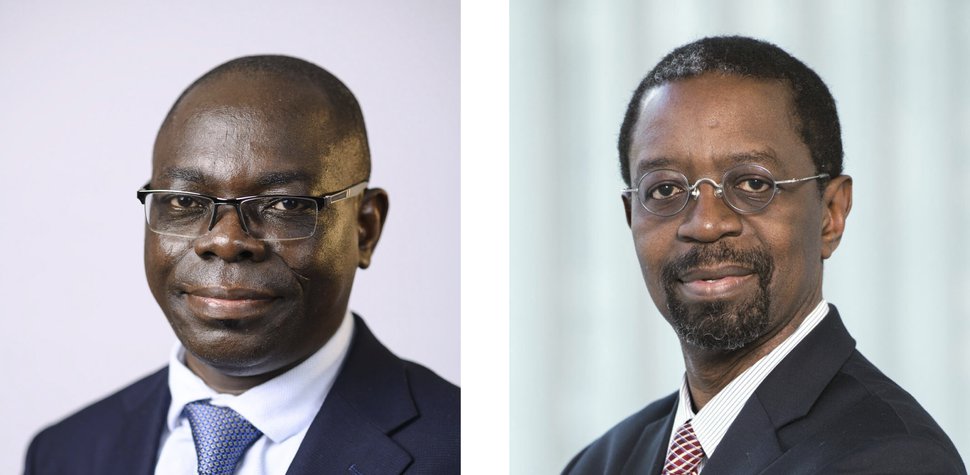

Justice Nonvignon (left) is is Head of Health Economics and Financing Program at the Africa CDC and Professor of Health Economics at the University of Ghana. Olusoji Adeyi is President of Resilient Health Systems and Senior Associate at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

After decades of lofty promises, mixed successes, catastrophic failures, and billions of dollars spent, the time is ripe to fundamentally change the construct and duration of global health grant-financing institutions and initiatives (GHIs). We acknowledge that GHIs – including multilaterals, bilaterals, and foundations – have contributed to some short-term progress in health service delivery and elements of health system development in Africa, but there remain questions about the sustainability of such progress. Our reflections and propositions address the more fundamental issue of medium-to-long term effects of the GHIs’ status quo on Africa: given the power imbalances and collective dysfunctions of GHIs, cui bono? In seeking answers to this puzzle, we encourage readers to ponder the implications for global health of Wole Soyinka’s searing wisdom: “Truth for me is freedom, is self-destination. Power is domination, control, and therefore a very selective form of truth, which is a lie.”

Design failure

Several considerations underpin our proposition. First, the GHIs share a fundamental design flaw – they were established with no end date. Implicit in that construct is an expectation of indefinite financing for potentially limitless demand, constrained only by how much donors were willing and able to spend, the “extractive capacity” of GHIs, and the “absorptive capacity” of recipient countries. Second, as stated in a recent article we co-authored, the legacy construct of foreign aid for health is fundamentally wrong. Externally modelled burden of disease estimates combine with externally driven cost-effectiveness estimates that often lack contextual relevance to inform externally inspired packages of essential health services that are marketed as “best buys.” GHIs, largely funded and controlled by a small group of countries and private foundations, then concentrate on paying for various portions of those best buys. Since money is fungible, foreign aid quantitatively displaces what should be country budgets, and its dynamics qualitatively displace essential policy processes within countries.

Design failures are compounded by failures of execution, unintended consequences, and perverse incentives. For example, there are no firewalls between funding by GHIs and de facto lobbying by GHIs for beneficiary countries to seek their financing and services. This has caused iterations of supplier-induced demand. Prominent leaders of some GHIs, private and public alike, routinely use their access to African heads of state and government to push the prioritization of programs to eliminate their preferred disease. Such actions effectively serve to launder the preferences of external parties, thereby short-circuiting country policy processes and preferences. Furthermore, by centering external entities as drivers of investments for disease control in Africa, donor financing confers legitimacy on remote control as a substitute for real collaboration. For example, it is unwise to lavishly finance health research institutions in Europe and North America to design and drive research in Africa when their functions could be done in Africa by Africans who combine technical expertise with the credibility of knowing realities on the ground – and at a fraction of the cost expended on the Western institutions. With major gaps in data, distant entities often rely on opaque models. Such models may confer a veneer of quantitative respectability on suspect data, but they merely serve to sway global health discourse and policies based on conjectures and surmises. Finally, GHIs with indefinite lifespans are prone to adventurism that is devoid of leadership accountability, intellectual rigor, and demonstrable track records.

A pernicious tango

We posit that donors who fund and control global health institutions know that the legacy system is unfit for the purpose of sustainable improvements. That is evident from, among others: a recent official signal that Norway is rethinking its silo approach to global health financing; the British government’s uncertainty about what it should do; tepid signs of “localization” by USAID; and several entities’ post-pandemic statements of commitment to African vaccine self-sufficiency after their unhelpful conduct during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The core problem is that donors, who fund and control the GHIs, have neither the political incentives nor the political courage to do the right thing, which is hard. Therefore, they recycle the easier things, which are wrong. That disposition is evident in two recent developments:

- One is the exercise that culminated in a report entitled “The Lusaka Agenda: Conclusions of the Future of Global Health Initiatives Process.” To its credit, it notes that the creation of new GHIs should be avoided. However, it failed to make a decisive shift from the status quo and offers no profound improvement. In seeking solutions “within existing structures and systems to address both today’s and tomorrow’s needs,” it shows neither strategic awareness of how broken the status quo is nor transformative purpose required for future success. After much convening and consultation, many of its conclusions seem to recycle exhortations for better donor alignment and country leadership, which were the staple of prior agendas and declarations from Paris to Busan to Accra, among others.

- The second example is a recommendation of The Lancet Commission on lessons for the future from the COVID-19 pandemic, which called for a new Global Health Fund to be headquartered in Geneva. After more than two decades of cultivating a Global Health Leviathan Cluster in Geneva, the recommendation reveals the perennial dominance of power over truth, combined with failure to learn and refusal to change. It is not prudent to replace a dysfunctional GHI oligopoly with a GHI monopoly because the latter is virtually guaranteed to be even worse than what it would replace. But there is a logic to the folly: recycling and amplifying the status quo perpetuates the power of donors over a vast network of rent-seeking actors in global health and the political benefits that accrue from being patrons in that construct. When will this proliferation of GHIs end, and when will the focus truly be on empowering countries to drive and finance their own health agenda from domestic resources?

In preserving the status quo, donors have often been willing accomplices in many of the recipient countries of Africa. With variations, many of the countries have a track record of one or more of the following: poor tax revenue generation relative to GDP; low current health expenditure relative to total government expenditure; dependency on external financing for disease control commodities and maternal and child health services; and high out-of-pocket expenditures relative to total health expenditures. Many resource-rich African countries remain reliant on external largesse for basic elements of health services. Some African leaders wax poetic about self-reliance while deriving a large part of their Current Health Expenditure from foreign aid. Several repeatedly muddle through instead of decisively fixing their health financing challenges. As in the case of donors, there is an internal logic to the countries’ perennial dependency: why endure the challenging road to true independence when it is easier to permanently depend on others? But that reasoning is pernicious because the logic and legacy architecture of foreign aid for health are inherently bad for Africa and must change.

The proposition

So, what changes do we propose for donors?

- Set termination dates for GHIs. Beyond the 2030 target date for Universal Health Coverage, such donors should not finance routine disease control programs, maternal and child health services, and basic health commodities in Africa. Donors who argue otherwise are undermining the continent’s development. For a change, they should stop infantilizing African leaders and countries.

- Start a binding and transparent transition process that will conclude by that end date. This process should not be derailed by excuses by the GHIs or recipient countries. It is essential to avoid yet another “global goal” that is designed in New York or Geneva, with a new target date that prolongs continental dependency, diplomatically foisted on African countries, and backed by the same power dynamics that have served the continent so poorly.

- Make waivers for clearly extraordinary cases, such as countries affected by catastrophic natural disasters and populations adversely affected by war – and even those should be finite and explicit, with built-in end dates appropriate for each setting. For post-war situations, provide generous, short-term humanitarian relief on the one hand while avoiding their emergence into perpetual recipients of foreign aid.

- Invest in Africa’s capacity to independently manufacture diagnostics, vaccines, and therapeutics without being hobbled by intellectual property rights. This goes beyond having African firms serve as distributors or confining them to fill-and-finish stages of the manufacturing process, a matter about which several publicized announcements of agreements on technology transfer, including for malaria vaccines and mRNA technology, have been disturbingly coy.

- Invest in African research institutions and think tanks so that they acquire the depth and breadth that will sustain true independence. There is a need to endow entities that will do what is essential, not contingent upon instant gratification of donor preferences, and ultimately endure.

- Invest in regional efforts aimed at mobilizing resources for regional and country public health commons, such as the Africa Epidemics Fund. It is unfortunate that donors have yet to highlight the importance of this Fund, which would better serve the continent than creating and centralizing new Funds based in Western countries.

Finally, African leaders should rise to the occasion by taking responsibility. Facilitated by regional groupings such as the African Union, African governments should commit to and be held accountable for clearly setting and vigorously pursuing paths to independence from donor aid. Progress along those paths should be closely monitored by stakeholders, including the African Union.

Positive change is not only necessary; it is possible.

________________________________________________________

Olusoji Adeyi is President of Resilient Health Systems and Senior Associate at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He formerly served as Director of the Health, Nutrition, and Population Global Practice at the World Bank.

Justice Nonvignon is Head of Health Economics and Financing Program at the Africa CDC and Professor of Health Economics at the University of Ghana.

* The authors wrote this article in their personal capacities. Its contents should not be attributed to any institution with which they are associated.